The Long Game: Mental Health NGOs and Israel’s Public Systems

- Gila Tolub

- Jan 6

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 12

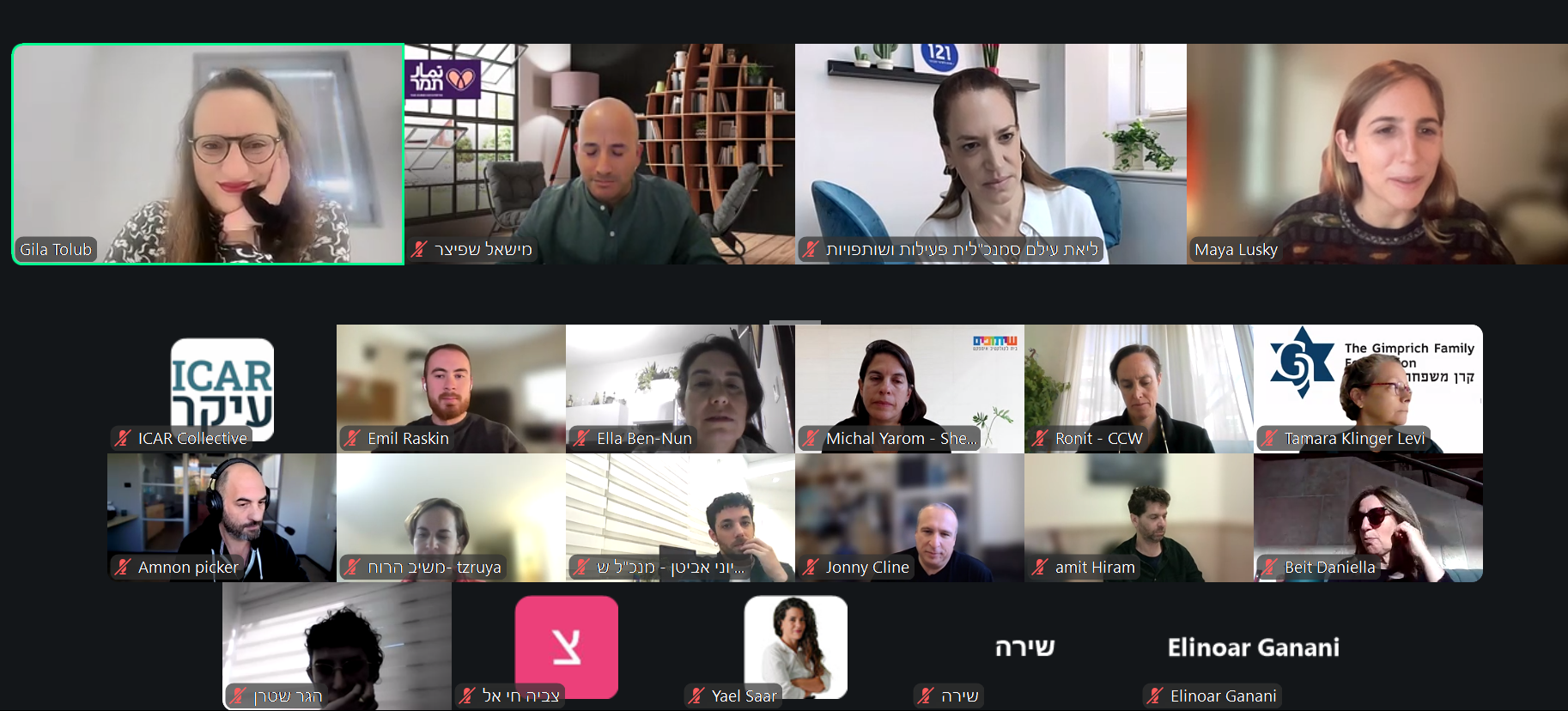

In a webinar moderated by Maya Lusky, Strategy and Research Manager at ICAR Collective, three practitioners, Liat Eilam, VP of Partnerships and Activities at 121 – Engine for Social Change; Michal Yarom, Deputy CEO at Sheatufim; and Jonny Cline, social impact strategist, nonprofit executive, and advisor, offered a grounded look at what it actually means to work with public institutions in Israel. Not in theory. In practice: ministries, municipalities, HMOs, and all the friction that comes with them.

Maya opened by naming why this topic matters. Many mental health organizations already work with public systems, or want to. They are looking for a realistic playbook. The promise is clear, scale, legitimacy, stability. The reality is more complicated.

The first mismatch: assuming the state naturally “gets” you

Jonny Cline described a common expectation gap. Nonprofits often assume that if something works, the state will eventually recognize its value and adopt it—almost as a natural next stage of maturity. The familiar storyline: start with an idea, prove it with early philanthropy, build momentum, and then the government takes it from there.

His point was blunt. That assumption often doesn’t hold. Not because public actors are malicious, but because the public system does not automatically recognize, prioritize, or move quickly on what civil society identifies as innovative or urgent. Expecting a smooth handoff can set organizations up for disappointment.

The second mismatch: treating your perspective as the default truth

Liat Eilam added another layer. Even when both sides care deeply about the same issue, they may see it through fundamentally different lenses. One recurring obstacle is the belief, sometimes subconscious, that our way of seeing the problem is the correct way.

That belief makes it harder to understand how a ministry or public agency frames constraints, incentives, and success. Collaboration, she emphasized, depends on something more practical than shared values: identifying a joint path of action. What can we actually agree on? Where can we realistically move together? Without that, “partnership” remains aspirational.

Policy work is real work—and it runs on a longer clock

Liat also named something many leaders feel but don’t always plan for. Organizations on the ground are overloaded—delivering services, managing crises, fundraising, often simultaneously. In that reality, policy work can feel abstract or impossible.

But it needs to be treated as a profession, not an add-on. It requires expertise, time, resources, and patience. The expectation that “we’ll work on it for a few months and it will happen” is, as she put it, unrealistic. Policy change moves slowly, and without capacity and a long-term horizon, organizations often disengage right before anything begins to shift.

A useful correction: government isn’t only bureaucracy and suspicion

Liat pushed back on another common belief—that government offices are primarily bureaucracy, and inherently suspicious of NGOs. She acknowledged that recent years, especially the war period, intensified distance and mistrust. But staying in a posture of critique, she argued, is not a strategy.

If you want partnership, you need curiosity. What pressures are they under? What rules are non-negotiable? What matters to them? What did they try before, and why did it fail? Those questions are not about being charitable. They are about building the conditions for joint action.

Systemic change in Israel requires public partnership—but not only at the national level

Michal Yarom framed the issue structurally. In Israel, public institutions shape so much of social life that real systemic change is impossible without working with them. The question is not whether to engage, but how—especially under instability, stagnation, and constant change.

Her practical point mattered: “working with the public sector” does not only mean ministries. There are multiple entry points—local authorities, regional councils, and other platforms—each with different advantages and constraints. Strategy means choosing where partnership is feasible, not insisting on one ideal channel.

Two partnership philosophies, and why sequencing matters

Liat described another approach to partnership. One that starts by building alignment within civil society first, deliberately keeping the government out of the room at early stages—not out of hostility, but to preserve independence and clarity.

“If they give me the first shekel,” she explained, “I need to be careful in what I say next to them.” Early alignment allows for honesty and mutual understanding before external pressures shape the agenda. The government is not to be ignored. Ministries are consulted in parallel, research is shared, and realities in the field are revealed. But the sequencing matters: align the field first, then engage the government from a stronger position.

The uncomfortable truth: the state often sees you as a vendor

The conversation then turned to a reality many participants recognized immediately. Even when NGOs initiate ideas, mobilize resources, and generate impact, public systems often still treat them as service providers—not partners.

Jonny questioned whether “full partnership” is even feasible. “If what you are doing is in their workplan”, he said, “they would do it themselves. The power asymmetry is real, and pretending otherwise can only cause dissonance”.

What is possible, he argued, is managing friction. Some friction sharpens thinking and clarifies roles. Too much friction, as he put it, “will burn the house down.” Knowing the difference is part of leadership.

When duplication becomes visible, and what it signals to the state

As the discussion continued, Maya raised a tension many leaders struggle with. The field is crowded. Many mental health organizations are doing important work, sometimes overlapping. With limited public attention and resources, the question becomes unavoidable: does duplication slow engagement with public systems?

Liat didn’t deny the reality. “I do see some duplications,” she said. But overlap itself isn’t the core problem. The deeper issue is how fragmentation looks from the state’s side.

When multiple organizations arrive with similar agendas—and sometimes strained relationships—it weakens the field’s position. From a ministry’s perspective, it becomes unclear who represents whom, and why anyone should commit.

Her conclusion was pragmatic. Before entering a policy process, they map the field carefully and engage only if they bring something genuinely distinct. If someone else is already leading effectively, the right move is reinforcement, not competition. “Amazing,” she said. “We’ll be happy to strengthen, happy to cooperate… and let them lead.”

Where coalitions do make sense, their impact is tangible. “When we come with sixty logos,” she explained, “they relate to us differently.” Not because of symbolism, but because it signals scale, coordination, and seriousness.

Coordination is what makes multiplicity workable

Michal reframed the duplication debate through collective impact. Complex social problems cannot be solved by one organization—or even by one sector. Multiple actors are inevitable. The risk isn’t multiplicity; it’s lack of coordination.

Each organization brings something unique. The challenge is to define a shared goal and organize action around it, with clear roles and synchronization mechanisms. Without structure, organizations step on each other’s toes. With it, diversity becomes strength.

She also reminded participants that systemic change unfolds across time and layers. “The last circle we expect to see,” she said, “is change at the population level.” That perspective helps explain why coalitions can feel slow even when they are doing necessary groundwork.

Duplication can shrink the pie, or force it to grow

Jonny added a strategic counterpoint. Yes, when funding is limited, more organizations can mean thinner slices of the pie. But duplication is not inherently inefficient. In practice, no two organizations are truly identical. Even similar models operate in different geographies and populations.

Multiplicity can also make scale visible. “It shows decision-makers this isn’t just happening in one place,” he said. “It’s broader. It’s a macro phenomenon.” That visibility can be what shifts an issue from a local NGO concern to something the state must address systemically.

What this leaves leaders with

This conversation didn’t offer slogans. It offered realism.

Working with public institutions does not automatically mean partnership. Often it means contracts, service provision, and imbalance. Coalitions do not magically solve this—but without them, credibility is weaker. Duplication is not inherently bad; uncoordinated fragmentation is.

The work is strategic, slow, and relational. It requires clarity about when to act independently, when to align, and when to engage the state—not based on wishful thinking, but out of a realistic understanding of how systems actually move.

In Israel, public-sector partnership, whilst not the right path for every NGO, is often the only path to systemic change. But how you approach it determines whether you build something durable—or spend years running up against with the same wall.

Comments